As someone who has spent years working with global brands, I’ve developed what I jokingly call a professional reflex. Whenever I see a product or service – be it a marketing campaign, a brand name, a piece of UX – I instinctively ask: How would this land in France? Or in Brazil? Or Japan?

It’s a habit I’ve picked up over time, and by now it feels more like instinct than conscious analysis. Call it an obsession, or maybe a kind of trained empathy. Whatever it is, it’s always running in the background.

So when generative AI tools exploded into the mainstream, it was only natural that I began wondering how they might land differently around the world. Not just in terms of the languages they support or the accents they mimic, but the deeper assumptions behind how they speak, suggest, decide, and behave.

Would people in different countries feel comfortable with the way AI chats with them? Would it come across as friendly or intrusive? Empowering or alienating? Would it understand local humour? Would it know what not to say?

More importantly…would people trust it?

I find myself asking a different kind of question these days, knowing full well the answers are complex. Because this time, we’re not just localising products or messaging. We’re localising intelligence.

The AI Index Report Confirmed What I Suspected

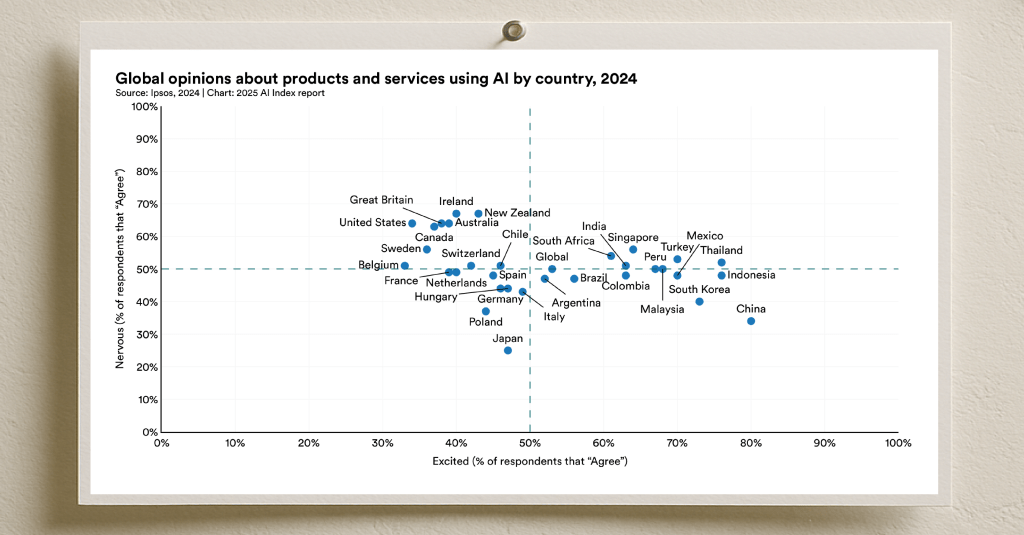

I recently came across the 2025 AI Index Report, which offers a compelling snapshot of global public opinion on AI – and reveals deep regional divides in how its benefits are perceived.

In countries like China (83%), Indonesia (80%), and Thailand (77%), strong majorities see AI as offering more benefits than drawbacks. Contrast that with Canada (40%), the U.S. (39%), and the Netherlands (36%), where public sentiment remains far more sceptical. And even in places where optimism is growing, concerns around fairness, bias, and trust remain stubbornly persistent.

This disparity is telling. It suggests that people are not responding to AI in the same way everywhere – and that those responses are shaped not just by access or infrastructure, but by something more layered: cultural context, historical memory, societal norms, and collective trust.

AI, in other words, isn’t a neutral technology moving through the world. It’s a phenomenon being interpreted through different lenses – and carrying different meanings as it does so.

AI Doesn’t Have a Global Image. It Has Many.

What struck me most from the report was this: AI, when productised, doesn’t behave like a single brand with a uniform reputation. It’s not Coca-Cola. It’s not the iPhone.

Instead, it’s a fragmented phenomenon – perceived as liberating in one country, suspicious in another, potentially job-threatening here, and educational there.

This fragmented global reception has profound implications for how AI products are built, marketed, adopted, and governed.

Let me illustrate a few thoughts on how this plays out across different domains:

For AI startups, the typical focus is on functionality and scale. But if AI’s meaning shifts from culture to culture, product-market fit must also include a “cultural trust fit.” Messaging around innovation, productivity, or augmentation needs to be contextualised: is AI seen as empowering? Intrusive? Inevitable? Alienating? Startups entering new markets must do more than translate interfaces – they must translate intent. For example, a generative AI writing tool marketed in the U.S. might lead with productivity and creativity; in France, it may need to speak more to artistic integrity and cultural authenticity.

For consumer brands touting their “AI-first” transformation, there’s a risk in assuming AI always signals progress. Recent backlash faced by Duolingo and Klarna shows what happens when users perceive AI as replacing, rather than enhancing, the human touch. In low-optimism markets like Canada, the U.S., and the Netherlands, AI branding can trigger anxiety rather than excitement. Brands must learn to balance global AI positioning with local storytelling. In some markets, “AI-enhanced” may resonate more than “AI-first.” Bringing in local influencers, educators, or creators can serve as cultural bridges that build trust.

Let’s Talk About Model Behaviour

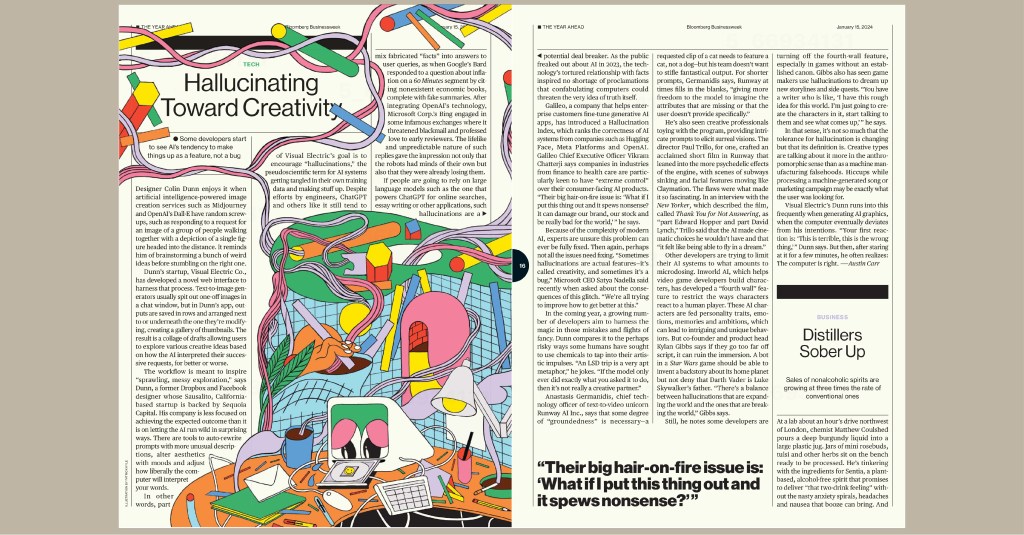

If the perception of AI varies across cultures, then surely the behaviour of AI models should reflect that too. And yet many of today’s most powerful systems – ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini – are trained largely on English-language, Western-centric data. They perform impressively across languages, but that doesn’t mean they grasp cultural nuance or behavioural expectations.

Translation isn’t localisation. Speaking a language correctly isn’t the same as knowing when to be formal, when to show deference, or when to exercise restraint. Tone, timing, and formality are culturally constructed.

An AI assistant that’s optimised for American norms might interrupt too quickly in Japan—or sidestep topics that, in another context, are essential to address. What’s seen as helpful in one country might be interpreted as evasive or inappropriate in another.

We’ve long accepted that brands need regional voices. Why shouldn’t AI?

Model Builders Are Starting to Pay Attention

For a while, it seemed this challenge was being overlooked in the rush to scale. But lately, signs of change are emerging.

At VivaTech 2025, I listened to a keynote by Jensen Huang, CEO of NVIDIA. To my surprise – and relief – he raised many of the same questions that had been circling in my mind. His talk focused on digital sovereignty and global ecosystems, and he laid out a vision in which AI models aren’t one-size-fits-all, but rather regionally grounded, culturally intelligent, and ethically plural.

He introduced NeMoTron, NVIDIA’s initiative to support the development of open, adaptable, region-specific large language models. It marked a significant shift – not just technically, but ideologically.

Rather than striving for a universal model that behaves the same everywhere, NeMoTron is built to be adapted, linguistically, behaviourally, even ethically, to suit local needs. It can be fine-tuned on proprietary data, embedded with national regulatory frameworks, and enriched with historical knowledge often missing from Western-centric training sets.

When paired with Perplexity, a partner focused on grounding AI responses in local sources, linguistic norms, and real-time cultural cues, we start to see a future that’s not just intelligent, but pluralistic by design.

From Brand Strategy to Model Design: A Common Lesson

In many ways, this mirrors what global marketers have long understood. The most successful global brands don’t impose one voice across every market. They build a strong, consistent identity, but they allow that identity to flex and adapt.

The same principle should apply to AI.

The goal isn’t to splinter AI into dozens of incompatible systems. It’s to build modular, configurable, and culturally fluent AI experiences that reflect the richness of human difference.

That means:

Rethinking alignment – not as a universal doctrine, but as something to be co-created with local communities.

Designing model behaviour – not just training data – with cultural values in mind.

Embedding localisation not just in content, but in the AI’s tone, persona, and ethical framing.

Toward a Culturally Attuned Intelligence

AI is fast becoming a companion technology – a tool we speak to, and that speaks back. As it takes on this role, the question isn’t just whether it understands us, but how well it reflects who we are, where we are, and what matters to us.

Cultural nuance isn’t an afterthought. It’s the foundation of trust, usability, and relevance.

If AI is to earn its place as a meaningful presence in everyday life, it must learn to do what any respectful guest in a new place does: listen first, speak with care, and adapt to the room.

It’s not enough to build intelligent systems.

We need to build attuned ones.

You must be logged in to post a comment.